Look at This! See How Walker Evans Plays with Space and Time

Walker Evans (1903–1975), an American photographer, is best known for his work documenting the Great Depression and its effects. Those photographs were commissioned by the Farm Security Administration (a government agency), but Evans’s documentary style pre-existed the work.

In contrast to artistically-oriented photography, which had been popular, Evans favoured an unsentimental approach, eschewing dramatic vantage points and mood-enhancing shadows. Evans photographed what he saw in a direct way, creating art by emphasizing the rhythms, textures, and organization of everyday life.

This photograph is a classic example of what Evans could do with an everyday moment that we might otherwise pass by without note:

What Does the Photo Tell Us?

We know from the caption that the scene is a dry goods store in 1936. Everything else is layer upon layer of emotional subtly.

How Does This Photo Make You Feel?

The calendar hanging in the top right of the frame provides us with the date and time stamps the photo. The calendar stops time, in every sense of the expression. The page will not turn; the date cannot be misconstrued and is irrevocably tied to the scene. Yet, at the same time (and I use that word deliberately), a calendar barely visible in the background displays the month of January—a conflict with the more obvious display of July on the calendar in the foreground. Did Evans deliberately include the second calendar in the photo as a nudge to remind us that while time might appear stopped, it is all, really, just an illusion? Is time is fluid after all?

Structure and The Fluidity of Passing Time

Evans chose to orient his camera to look directly into the room. Doing so, he manages to create great tension between stopped and

fluid time. He has organized his photo so that a spilled box and a skewed bag of

seed take notice in the midst of carefully organized, highly structured space.

Everything but those two items is neat, tidy, and still.

Evans reinforces the store’s aligned and stable organization with square, direct framing of the scene—achievable with such precision only with the use of a large format view camera. The photograph is in focus from front to back. Including the edge of the table as a leading line in the lower left of the photograph—that length of table also being in focus from front to back—adds to Evan’s precise re-creation of organized three-dimensional space. We don’t need to see the aisle behind the stacked bag of seeds to know that it’s there; that’s how accurately Evans managed to re-create the space. The “O.K.” stamped on the soap boxes is a visual affirmation of the security and solidity generated by a store of plenty, organized so that customers can easily identify what they may need and obtain it.

Evans also uses every available visual line in the scene—all

precisely aligned—to reinforce the sense of solid, stable space. The poster for

Coca-Cola hanging in the top left of the frame is perfectly squared within the

frame, like a postage stamp visually reinforcing the edges. The vertical

supports of the shelves, structural post, stacks of dishes, stacks of seed, and

upright precision of the lanterns provide the vertical lines of a grid. The

shelves themselves and the rows of boxed supplies on the shelves, the white

cover under the table of dishes, the top of the stacks of seeds, and the top of

the wooden cabinet behind the seeds all provide the horizontal lines of a grid.

Even the ladder back of the chair just visible in the bottom right of the photo

add to the grid construction. Then, to make that grid three-dimensional, Evans

uses the leading edge of the table on the left, the floorboards and ceiling

boards to create the space from front to back. Note that those lines from front

to back are the only converging lines in the photograph, which strengthens our

perception of depth.

Transcendent Timelessness of a Suspended Moment

And then in the middle of that precise grid, we have a

dropped and spilled box and a bag of seed slightly askew. They are small items

in a photograph filled with detail, but their placement in our visual center of

the scene ensures we will notice them. This dry goods store has been “caught in

the act,” as it were. The store has not been especially prepared for a

photograph; rather, the store owner has briefly stepped aside while Evans

captured the ordinary precision and pride of the store’s organization.

I can’t help but think that in the midst of this careful organization, Evans noticed the discrepancy between the two calendars and composed his photo in such a way that the calendars injected a teasing note. They, along with the spilled box and skewed bag of seed, are the notes that ensure that an otherwise stolid composition continues to pulse.

Your Turn to Spend a Little Time with Walker Evans

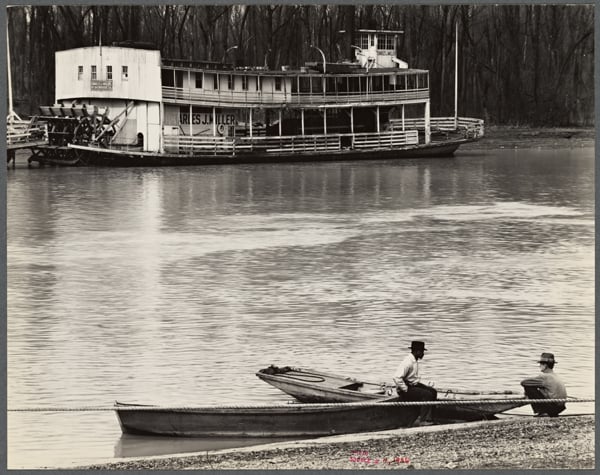

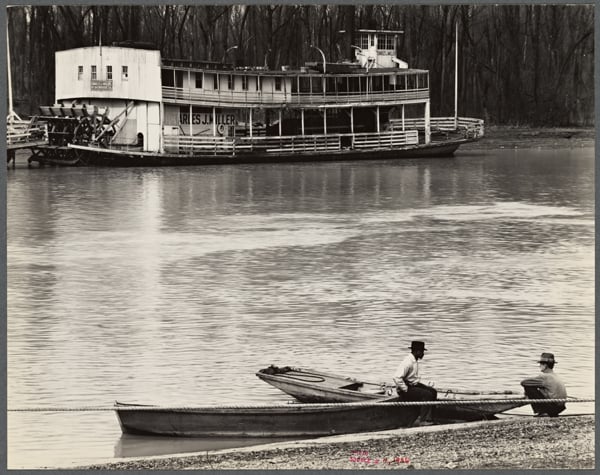

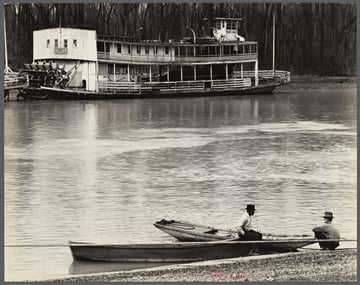

The photograph below is another by Walker Evans. We know the date is 1936 because it’s written on the photo in red ink. The compositional elements in this photograph are more fluid (it even contains water) and less architectural but no less evocative. How does Evans use the organization of space to create the tension between stability and movement in this photograph?